This blogpost summarizes recommendations for policy makers and explores 3 good practices for equitable remote learning, based on recent research conducted using data on education responses to COVID-19 from UNICEF staff in 127 countries.

To help contain the spread COVID-19, schools have closed around the world, at its peak putting approximately 1.6 billion or 91% of the world’s enrolled students out of school (UNESCO). Governments and education stakeholders have responded swiftly implementing remote learning, using various delivery channels, including digital tools, TV/radio-based teaching, and take-home packages. The massive scale of school closures has laid bare the uneven distribution of technology to facilitate remote learning and the lack of preparedness of systems to support teachers, and caregivers in the successful and safe use of technology for learning.

Key recommendations to education policy makers for COVID-19 and beyond:

- Education systems need a ‘Plan B’ for safe and effective learning delivery when schools are closed. Producing accessible digital and media resources based on the curriculum will not only allow a quicker response, but their use in ordinary times can enrich learning opportunities for children in and out of school.

- Infrastructure investment in remote and rural areas to reach marginalized children should be a priority. Initiatives like Generation Unlimited and GIGA, can democratize access to technology and connectivity, increasing options for remote learning delivery and speeding up response during school closures.

- Teacher training should change to include management of remote ‘virtual’ classrooms, improving presentation techniques, tailoring follow-up sessions with caregivers and effective blending of technology into lessons.

- Further applied research for learning and sharing what works is more important than ever. Increased focus on implementation research is needed to develop practical ways to improve teacher training, content production, parental engagement, and to leverage the use of technologies at scale.

Practices for more equitable remote learning

Given the digital divide use multiple delivery channels

Large inequities exist in access to internet around the world as illustrated by figure 1 below. Governments are increasing access to digital content for children where possible, by negotiating to not charge data costs for education content (Rwanda, South Africa, Jordan).

Even with initiatives to increase access in the short-term, digital channels are not enough to reach all children, especially the most disadvantaged as explored in Remote Learning Amid a Pandemic: Insights from MICS6. To expand their reach, 68% countries are utilizing some combination of digital and non-digital (TV, Radio, and take-home packages) in their education responses.

Even with initiatives to increase access in the short-term, digital channels are not enough to reach all children, especially the most disadvantaged as explored in Remote Learning Amid a Pandemic: Insights from MICS6. To expand their reach, 68% countries are utilizing some combination of digital and non-digital (TV, Radio, and take-home packages) in their education responses.

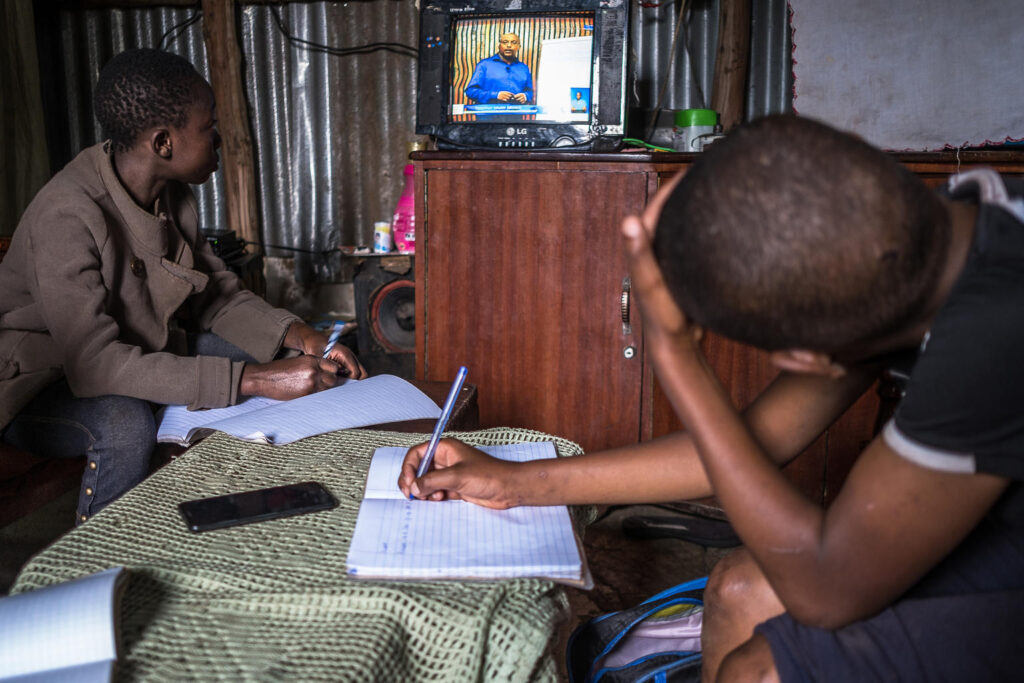

TV is being used by 75% of countries, including making TV lessons accessible for children with hearing impairments with sign language (Morocco, Uzbekistan). Radio is also a widely used tool, 58% of countries report using it to deliver audio content. However, digital, tv and radio delivery channels all require electricity. Simple (unweighted) average of the 28 countries with data by income level, shows that only 65% of households from the poorest quintile have electricity, compared to 98% of households from the wealthiest quintile. In seven countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Lesotho, Kiribati, Sudan, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, and Mauritania) less than 10% of the poorest households have electricity.

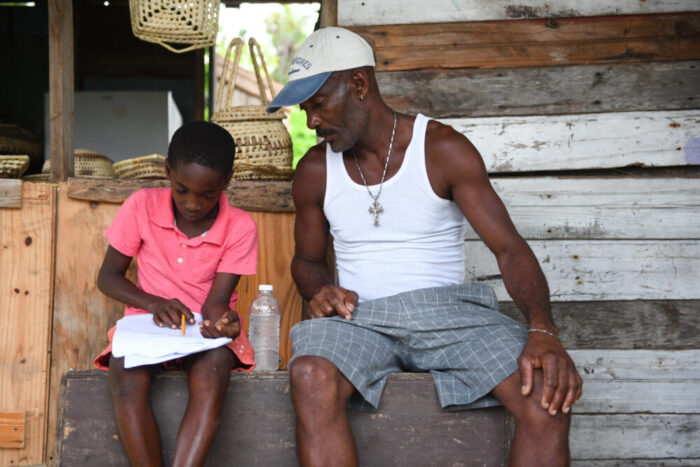

To address this challenge, 49% of countries are also using “take home” packages for learners. In Jordan, refugee children are receiving learning packages and in Jamaica learn and play kits are delivered to children in quarantined zones. Parental engagement is critically important for learning and should not be overlooked as explored in the recent research brief on parental Engagement in Children’s Learning – Insights for remote learning response during COVID-19

Figure 3. Below shows the wide disparity in Radio ownership across 88 countries, while figure 4 illustrates the urban rural gap in TV ownership within countries.

Strengthen support to the teachers, facilitators and parents delivering remote learning

Strengthen support to the teachers, facilitators and parents delivering remote learning

Access to content is only the first step in remote learning. Countries are supporting caregivers who have been thrust into teaching at home, with tutoring materials, webinars/helplines to answer their questions (North Macedonia, Uruguay). Countries are engaging with caregivers, to not only support learning but to, provide psychosocial support to children (Bhutan, Cameroon, Ecuador, Eswatini, Guatemala, Oman, India), provide tips for children’s online safety (North Macedonia, Serbia) and engage with families to allow girls to continue learning remotely rather than increasing their household duties (Ghana).

Gather feedback and strengthen monitoring of reach and quality

Gather feedback and strengthen monitoring of reach and quality

Countries have engaged in a variety of measures to collect feedback, and to understand the usage and effectiveness of different delivery channels. Monitoring of reach and quality for remote learning remains a challenge for many countries. While there is great need to understand how COVID-19 has impacted children, education actors must take care to ensure that any data collection exercise from children follows ethical considerations and, first and foremost does no harm (Berman, 2020). Several countries are using simple tools (SMS in Tanzania, Chatbots in Mongolia) to gather feedback from parents to improve remote learning. Serbia, South Africa, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan have incorporated assessment tools within digital platforms.

Thomas Dreesen is an Education Manager at UNICEF’s Office of Research (OoR), Mathieu Brossard is the Chief of Education at UNICEF OoR- Innocenti. Spogmai Akseer, Akito Kamei and Javier Santiago Ortiz are education research consultants at UNICEF OoR- Innocenti, Pragya Dewan is a consultant in the education section of UNICEF’s programme division, Juan-Pablo Giraldo is an education specialist in UNICEF’s Programme division, and Suguru Mizunoya is a Senior Advisor in statistics and monitoring with UNICEF’s Data and Analytics team.