Children engaged in child labour from poor households – even those attending school – are at risk of being left behind when it comes to their learning outcomes.

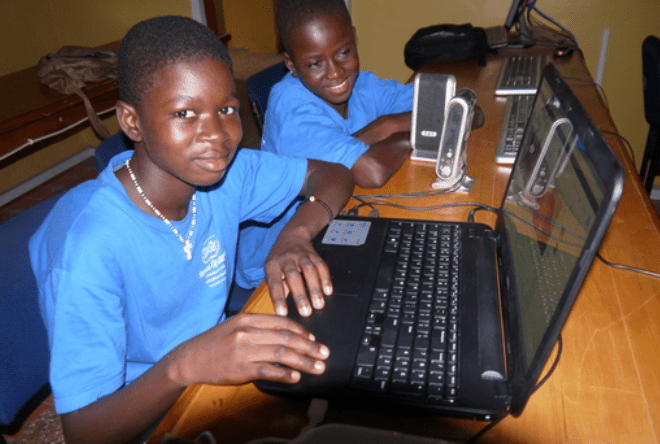

Noah Oletey, aged 12, and his brother Vincent, aged 14, work six nights a week on fishing canoes on Lake Volta in Ghana. Noah and Vincent attend school, but only when their work schedule permits it and they have enough money to pay their school fees. As such, their educational opportunities are limited, and their performance at school suffers.

The story of Noah and Vincent shows that engaging in child labour can be negatively associated with school attendance and the acquisition of vital foundational learning skills.

UNICEF-supported Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) capture data both on children’s learning and child labour, providing valuable statistical insights on the relationship between two important SDG indicators, SDG 4.1.1(a) and SDG 8.7.1 (see box below).

The sixth round of MICS (MICS6) introduced a new foundational learning skills module that measures reading and numeracy among children aged 7 to 14 years who are both in and out of school. The MICS6 questionnaire also collects information on children’s involvement in economic activities and household chores, and their exposure to hazardous working conditions.

Both child labour and learning skills are covered in Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) indicators. SDG 4.1.1.(a) measures the proportion of children in Grades 2 or 3 who achieve at least a minimum proficiency level in reading and numeracy; SDG 8.7.1 measures the proportion of children aged 5 to 17 years who are engaged in child labour.[1]

Child labour refers to children’s engagement in activities are detrimental to their physical, social, psychological or educational development. The guiding international conventions on this issue are the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 138 on the minimum age for admission to employment and work, ILO Convention No. 182 on the worst forms of child labour, and the International Convention on the Rights of the Child.

For the purpose of SDG monitoring, child labour is measured in terms of the percentage of children aged 5 to 11 years who are engaged in at least one hour of economic activities or 21 hours of unpaid household services per week; children aged 12 to 14 years who are engaged in at least 14 hours of economic activities or 21 hours of unpaid household services per week; or children aged 15 to 17 years who are engaged in at least 43 hours of economic activities per week.

Children from poorer households face learning challenges

As seen in Figure 1, results from 13 low- and middle-income countries [i] illustrate a stark reality: children from poor households are less likely to have foundational reading skills, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa where the vast majority of children are not learning the most fundamental reading skills. Unsurprisingly, this is also generally true of children who do not attend school (not shown).

Figure 1. Percentage of children aged 7 to 14 years who demonstrate foundational reading skills, by wealth

Source: Authors’ calculations based on MICS6 data for various countries, 2017-2019.

Notes: In Kiribati and Mongolia, confidence intervals at the 95 per cent level overlap between two wealth groups.

Children from poorer households and those not attending school are more likely to be engaged in child labour

The figure below shows that poorer children and children who are not in school are more likely to be engaged in child labour than their wealthier counterparts and children who are attending school. However, the data also show that many children from relatively rich households and those who attend school are also engaged in child labour, suggesting a complex relationship among school attendance, child labour and household wealth.

Figure 2. Percentage of children aged 7 to 14 years who are engaged in child labour, by wealth and school attendance

Source: Authors’ calculations based on MICS6 data for various countries, 2017-2019.

Notes: In Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kiribati and Suriname, confidence intervals at the 95 per cent level overlap between two wealth groups (left figure). In Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kyrgyzstan, Kiribati, Mongolia and Suriname, confidence intervals at the 95 per cent level overlap between children who are attending and not attending school (right figure).

Child labour is associated with poor learning

In order to understand how child labour and learning outcomes interact, a regression analysis was conducted to find associations between child labour and foundational learning skills.[ii] Figure 3 presents the likelihood of children aged 7-14 years having foundational reading skills (y-axis) by their age (x-axis). The red and blue lines represent those who are engaged in child labour and those who are not, respectively. In most countries, the red lines lie below the blue ones, suggesting that children in child labour lag significantly behind in foundational learning skills. In addition, the gaps between children engaged in child labour and those who are not widen as children become older.

Figure 3. Probability of demonstrating foundational reading skills among children aged 7 to 14 years, by age group and child labour status

Source: Authors’ calculations based on MICS6 data for various countries, 2017-2019.

Notes: Children who have only attended early childhood education programmes or the first grade of primary school are excluded, since the foundational learning module tests for skills at the Grade 2/3 level. Light coloured bands represent 95% confidence intervals. Suriname’s results are not presented since prediction of children who are engaged in child labour (red) in all age groups are based on less than 25 cases.

Children who are poorer and engaged in child labour demonstrate lower foundational reading skills than those who are richer, not engaged in child labour and attending school

In light of the SDG commitment to leave no one behind, we further disaggregated the results by wealth and school attendance.[iii] Figure 4 presents clear messages. The gap between the red lines, representing children from poor households who attend school, and the blue lines, representing children from rich households who attend school, is wide for most of the countries.

Furthermore, the gaps remain constant or increase for older children, suggesting that learning gains are limited for children engaged in child labour even if they are in school. In countries with yellow lines, representing children from poor households who are out of school, the yellow line is located below the other lines – showing the linkage in child labour, and poor learning outcomes.

Figure 4. Probability of demonstrating foundational reading skills among children aged 7 to 14 years, by age, child labour status, wealth and school attendance

Source: Authors’ calculations based on MICS6 data for various countries, 2017-2019.

Note: Children who have only attended early childhood education programmes or the first grade of primary school are excluded, since the foundational learning module tests for skills at the Grade 2/3 level. Light coloured bands represent 95% confidence intervals. The estimates are presented when they are predicted based on 25 or more cases in more than one age group. Suriname’s results are not presented since prediction of poorer children who are engaged in child labour by school attendance (yellow and red) in all age groups are based on less than 25 cases.

Building the economies of the future depends on ensuring children are learning today

The current COVID-19 pandemic is already affecting children in ways that reach beyond direct health outcomes. In a recent survey conducted in Thailand, more than 80 per cent of adolescents reported being worried about their household income, while in another poll, more than 85 per cent of Senegalese declared they have already observed decline in income. It is estimated that 85 to 420 million people will fall into extreme poverty of the USD 1.9 per day poverty line compared to 2018 as a result of the crisis. Recently, UNICEF and ILO published a report warning that the number of children engaged in child labour globally may reverse course and increase for the first time in 20 years.

Research on past economic crises suggests that the added economic burden placed on many families and caregivers can make children more vulnerable to exploitation,[iv] with corresponding negative impacts for children’s education. Ensuring that all children can acquire foundational learning skills is critical if countries are to build the human and intellectual capital necessary to create strong economic growth. We must not lose sight of the special challenges children engaged in child labour face, and take extra steps to help them learn and prepare for the future.

References:

[i] The 13 countries with both foundational learning and child labour modules in MICS6 are Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Gambia, Kiribati, Kyrgyzstan, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mongolia, Sierra Leone, Suriname, Togo and Zimbabwe.

[ii] The probability is estimated based on a logistic regression model that uses child labour, the average age of each age group, wealth and school attendance as predictors and foundational reading skills as an outcome variable.

[iii] The probability is estimated based on the same model as Figure 3.

[iv] See: Beegle, Kathleen, Rajeev H. Dehejia and Roberta Gatti, “Child Labor, Crop Shocks, and Credit Constraints,” NBER Working Paper no. 10088, November 2003; Guarcello, Lorenzo, Fabrizia Mealli and Furio Camillo Rosati, “Household Vulnerability and Child Labour: The effects of Shocks, Credit Rationing and Insurance,” Social Protection Discussion Paper Series no. 0322, World Bank, November 2003; Ravetti, Chiara, “The Effects of Income Changes on Child Labour: A review of evidence from smallholder agriculture,” International Cocoa Initiative, April 2020.