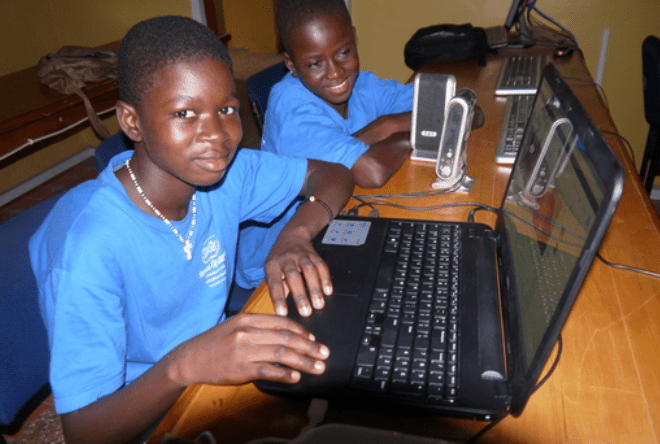

Data from household surveys show that many school-aged children, especially the most disadvantaged, do not have access to the internet at home.

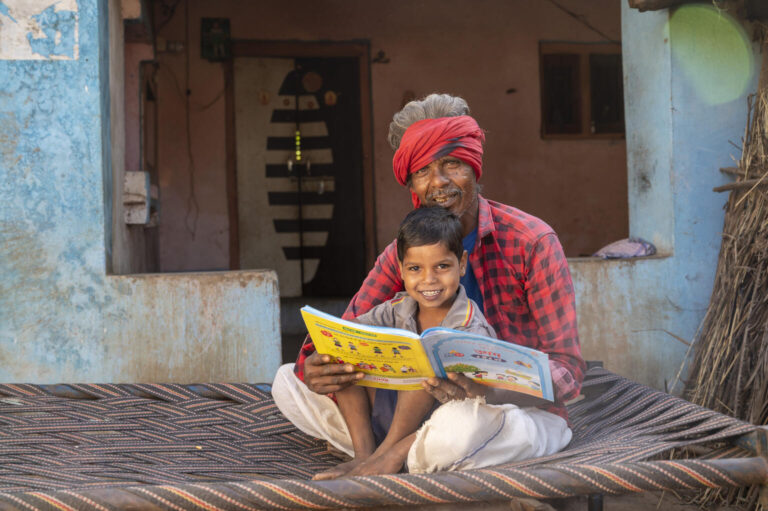

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused the largest disruption of education in modern history: at its peak, 1.6 billion children worldwide were affected by school closures. Although it’s been more than a year since the start of the global pandemic, and many countries have already reopened their schools, a recent UNICEF report suggests that more than 25 countries have kept their schools closed as of February 2021, preventing almost 200 million schoolchildren worldwide from attending classes in-person. In response to the unprecedented challenge posed by the pandemic, more than 90 per cent of the world’s education ministries have adopted various remote learning policies using the internet, television, radio and take-home packages to help children learn at home. Among these different modalities, online learning emulates in-person instruction the most, allowing interactions between teachers and students.

The report on digital connectivity estimates that 2.2 billion children and youth today under the age of 25 do not have fixed internet access at home. Building on previous work, this blog further explores digital connectivity at home among school age children (approximately 3-17 years old) and finds stark disparities in digital connectivity depending on socioeconomic status, location and region of the world. The digital divide poses additional challenges to ensuring equitable access to education for the world’s most disadvantaged and marginalized children under school closure conditions. Without addressing the gap in digital connectivity, the lack of access to the internet for these children could further exacerbate inequalities in education and learning.

See the database on school-age digital connectivity here.

Only one in three school-aged children has internet access at home worldwide, and significant disparities are observed by region

Household survey data, from Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) of 92 countries show that globally, children with higher levels of education are more likely to have internet access at home. And while in Eastern Europe and Central Asia almost an equal share of school-aged children have internet access, in East Asia and the Pacific, children in upper secondary school are much more likely to have access to the internet than those in primary school. Furthermore, in addition to differences by education level, regional disparities are substantial, with only 5 per cent of school-aged children in the West and Central Africa region having internet connections at home.

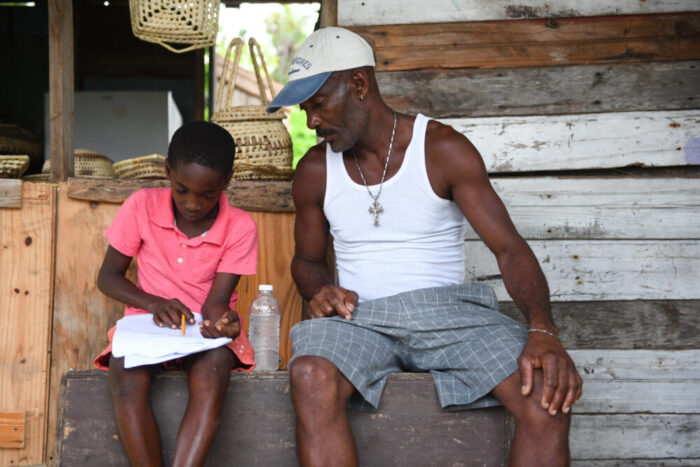

Place of residence and socioeconomic status strongly influence access to internet at home

Globally, 42 per cent of the children residing in urban areas have internet access, compared to 23 per cent of their rural peers. The urban-rural divide is most pronounced in the Latin America and Caribbean region, with a gap of 35 percentage points.

Strong inequalities associated with household wealth are even more concerning. Worldwide, roughly 60 per cent of children from their country’s richest wealth quintile are connected to the internet at home, whereas less than 20 per cent of the children from the poorest wealth quintile are. What’s particularly striking is that in West and Central Africa, South Asia and Eastern and Southern Africa, internet connectivity for the poorest children is almost non-existent.

The unprecedent disruption in learning due to COVID-19 underscores the importance of the resilience of education systems. Without effective action, the World Bank estimates that the substantial learning loss due to the pandemic will lead to a $10 trillion loss of lifetime earnings for affected children and youth. Furthermore, given the disparities in internet access, it’s likely that the most marginalized and disadvantaged groups will be hardest hit. Therefore, to prepare for future crises, urgent cross-sectoral efforts should be made to expand affordable connectivity for every learner. The benefits of these investments will go far beyond the needs of the education sector, providing substantial support for the most disadvantaged children in closing the digital divide.